I still remember the moment about 9 years ago when I first truly grasped the scale of economic inequality in our society. I was researching household finances for a community development project and came across a statistic that stopped me cold: the wealthiest 1% of households held more wealth than the bottom 90% combined. What struck me wasn’t just the numerical disparity but what it represented in terms of opportunity, security, and human potential. That realization sparked my ongoing interest in understanding both the causes of economic inequality and potential approaches to addressing it.

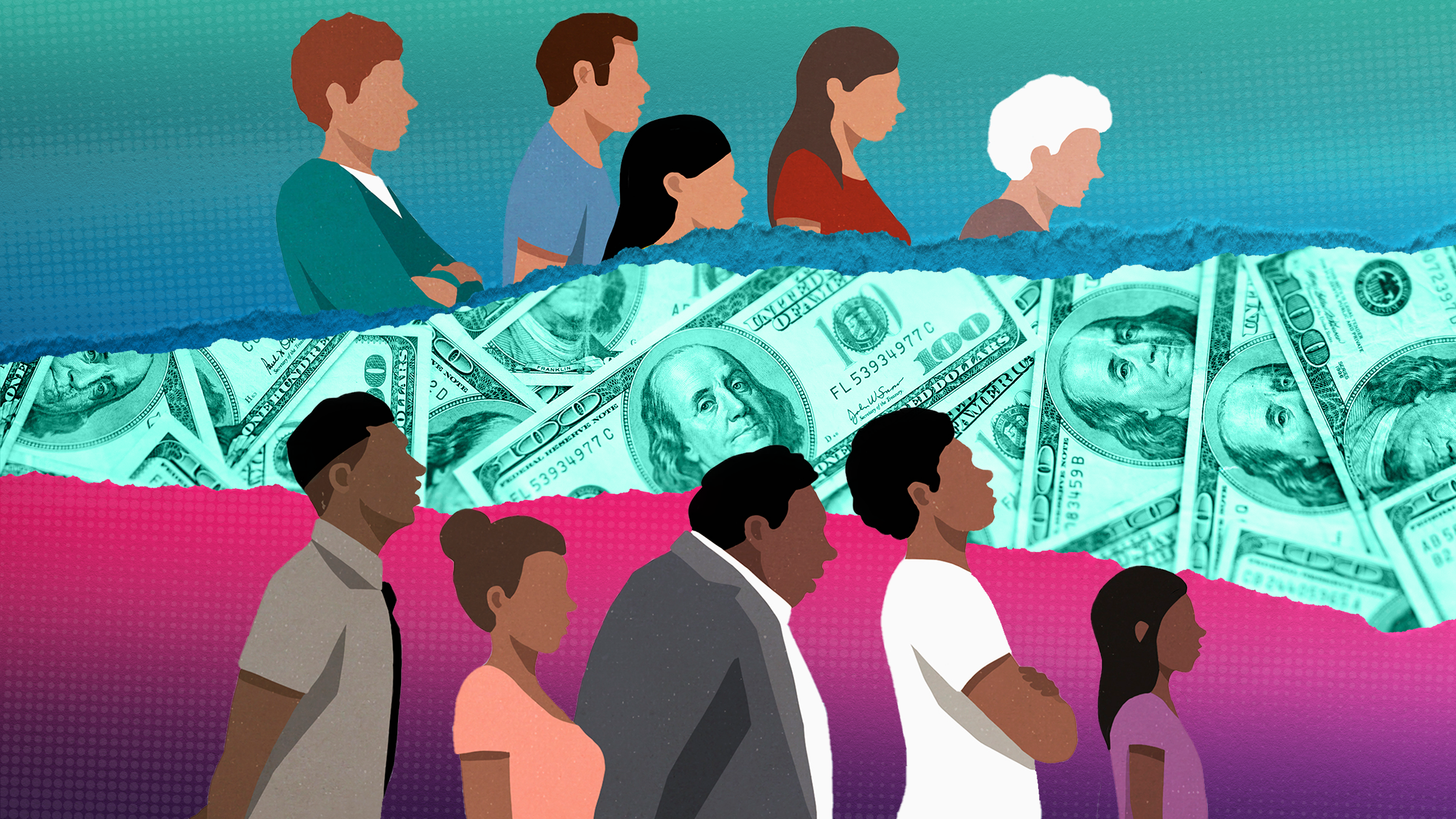

Economic inequality—the uneven distribution of income and wealth among individuals in a society—has increased significantly in many countries over recent decades. According to economic research, this trend has accelerated particularly since the 1980s, with wealth becoming increasingly concentrated among a smaller percentage of the population. Understanding the causes, consequences, and potential solutions to this growing wealth gap is essential for anyone concerned with creating more equitable and sustainable economies.

Understanding the Scope of Economic Inequality

Before examining causes and solutions, it’s important to clarify what economic inequality encompasses and how it’s measured.

Different Types of Economic Inequality

Economic inequality takes several forms:

Income inequality refers to disparities in the flow of money to different individuals or households, typically measured in annual earnings or wages.

Wealth inequality measures differences in accumulated assets minus liabilities—essentially what people own minus what they owe. Wealth inequality is typically much larger than income inequality because wealth accumulates over time and across generations.

Opportunity inequality relates to differing access to education, healthcare, employment opportunities, and other resources that enable economic advancement.

These forms of inequality are interconnected but distinct. For instance, two families might have similar incomes but vastly different wealth levels if one has substantial inherited assets or property appreciation. Similarly, children from families with identical wealth levels might face different opportunity landscapes based on factors like neighborhood quality, school systems, or social networks.

Measuring the Wealth Gap

Economists use several metrics to quantify economic inequality:

The Gini coefficient ranges from 0 (perfect equality, where everyone has exactly the same resources) to 1 (perfect inequality, where one person has everything). The United States has one of the highest Gini coefficients among developed nations, indicating greater inequality.

Income and wealth percentiles compare how resources are distributed across population segments. For example, examining what percentage of total wealth is held by the top 1% versus the bottom 50%.

Intergenerational mobility measures how easily individuals can move to a different economic position than their parents—essentially, whether children born into poverty can achieve middle-class or affluent status through their own efforts.

These measurements reveal concerning trends. In many developed economies, particularly the United States, wealth concentration has intensified dramatically since the 1980s. The share of wealth held by the top 0.1% has returned to levels not seen since the 1920s, while middle-class wealth has stagnated and economic mobility has declined.

Root Causes of the Growing Wealth Gap

Economic inequality stems from multiple interrelated factors. Understanding these causes is essential for developing effective approaches to reducing the wealth gap.

Structural Economic Changes

Several fundamental economic shifts have contributed to widening inequality:

Technological change and automation have increased productivity but often displaced middle-skill workers, creating a “hollowing out” of the job market with growth primarily in high-skill and low-skill positions.

Globalization has created new markets and opportunities but also facilitated outsourcing of manufacturing and some services to lower-wage countries, putting downward pressure on wages for certain sectors of the domestic workforce.

Shift from manufacturing to service economy has changed the nature of available jobs, with many service sector positions offering lower wages, fewer benefits, and less stability than the manufacturing jobs they replaced.

These structural changes aren’t inherently negative—they’ve created efficiency, innovation, and wealth—but their benefits and costs have been unevenly distributed, often exacerbating inequality.

Policy Choices and Institutional Factors

Beyond structural economic changes, specific policy decisions have influenced the wealth distribution:

Tax policy changes since the 1980s have frequently reduced top marginal income tax rates and taxes on capital gains, investment income, and inherited wealth. These changes have allowed faster wealth accumulation among high-income earners and those with existing assets.

Decline in labor unions and worker bargaining power has coincided with the growing gap between productivity gains and worker compensation. When unions were stronger, they helped ensure that economic growth translated into broader wage increases.

Financial deregulation expanded access to credit but also enabled more complex financial instruments that primarily benefited sophisticated investors while sometimes creating systemic risks borne by the broader public.

Education funding disparities perpetuate opportunity gaps, with schools in wealthy districts often receiving significantly more resources than those in lower-income areas, despite the latter frequently having greater needs.

Feedback Loops and Wealth Concentration

Perhaps most concerning are the self-reinforcing mechanisms that can accelerate inequality:

Capital returns vs. labor income: As Thomas Piketty documented in “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” returns on capital (assets like stocks, bonds, and real estate) have historically exceeded economic growth rates. This means those who already own substantial assets can see their wealth grow faster than those relying primarily on labor income.

Political influence: Concentrated wealth can translate into disproportionate political influence through campaign contributions, lobbying, and control of media outlets, potentially skewing policy in ways that further benefit the wealthy.

Intergenerational wealth transfers: Inherited wealth—which passes along advantages accumulated across generations—plays a significant role in perpetuating economic inequality. Even with identical incomes, families with inherited wealth can provide different opportunities to their children through housing in better school districts, college funding, down payments for homes, and safety nets during difficult times.

Consequences of Wide Economic Disparities

The impacts of severe economic inequality extend far beyond simple numerical differences in bank accounts. Research suggests widening wealth gaps create substantial costs for society as a whole.

Economic Consequences

Contrary to some assumptions, excessive inequality may actually hamper economic growth and dynamism:

Reduced consumer spending and aggregate demand: When wealth concentrates among those with lower marginal propensity to consume, overall spending may decrease, potentially reducing economic activity and job creation.

Underinvestment in human capital: When significant portions of the population lack resources for education, skills development, and basic needs, their productive potential remains untapped, reducing overall economic output.

Inefficient allocation of talent: When opportunities depend heavily on family background rather than ability, society loses the contributions of talented individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds while positions of influence may be filled by less capable individuals from privileged circumstances.

Financial instability: Extreme inequality can contribute to asset bubbles and excessive leverage as middle-class households borrow to maintain living standards amid stagnant wages, potentially increasing systemic financial risk.

Social and Political Impacts

Beyond purely economic effects, inequality affects social cohesion and political functioning:

Erosion of social trust: Societies with higher inequality typically show lower levels of social trust—the belief that most people can be trusted—which is associated with worse outcomes in public health, education, and governance.

Democratic dysfunction: When economic power translates into political power, democratic systems may become less responsive to the needs and preferences of the broader population, potentially undermining their legitimacy and effectiveness.

Social mobility barriers: Excessive inequality can harden into rigid class structures where birth circumstances predominantly determine life outcomes, contradicting ideals of equal opportunity and meritocracy.

Health and wellbeing disparities: Economic inequality correlates with significant disparities in health outcomes, life expectancy, and overall wellbeing, including for those in middle-income brackets.

The research on these consequences suggests that extreme inequality isn’t just problematic for those at the bottom—it can undermine economic performance, social cohesion, and institutional effectiveness for society as a whole.

Approaches to Addressing Economic Inequality

Addressing economic inequality requires multifaceted approaches rather than single policies. Here are key strategies that research suggests could help reduce the wealth gap while supporting broader economic health.

Education and Opportunity Enhancement

Education represents a crucial pathway for increasing economic mobility and reducing long-term inequality:

Early childhood education yields some of the highest returns on public investment, with quality pre-K programs showing long-term benefits for participants’ earnings, health, and social outcomes while reducing costs associated with remedial education, crime, and social services.

K-12 education funding reform to ensure resources align with student needs rather than local property wealth could help level the educational playing field and develop human potential more fully.

Higher education accessibility through affordable community colleges, public universities, and targeted support for first-generation college students can increase socioeconomic mobility.

Workforce development and lifelong learning systems to help workers adapt to changing skill requirements throughout their careers can prevent displacement and wage stagnation amid technological change.

While education alone cannot solve inequality—particularly when disparities in educational opportunity themselves reflect broader inequality—it remains a crucial component of any comprehensive approach.

Labor Market Policies

Several approaches can help ensure that work provides economic security and opportunity:

Minimum wage policies adjusted for regional living costs can establish wage floors that enable full-time workers to meet basic needs.

Collective bargaining strengthening through labor law reform could help workers receive compensation more proportional to their productivity contributions.

Worker voice and ownership through mechanisms like works councils, profit-sharing, employee stock ownership plans, and cooperative business structures can give labor stakeholders more influence over workplace decisions and a greater share of enterprise returns.

Employment supports like affordable childcare, paid family leave, and flexible work arrangements can increase labor market participation, particularly for caregivers who might otherwise face limited options.

Tax and Transfer Policies

Tax and transfer systems can directly address income and wealth disparities:

Progressive taxation of income, capital gains, and wealth can reduce post-tax inequality while generating revenue for public investments that expand opportunity.

Estate tax reform to effectively address large intergenerational wealth transfers could reduce the perpetuation of economic advantages across generations.

Expanded earned income tax credits or similar wage subsidies can boost incomes for low and moderate-wage workers while encouraging employment.

Universal basic income or related approaches like negative income tax could establish income floors while accommodating changing work patterns in an automated economy.

The specific design of these policies matters tremendously for their effectiveness and potential side effects—well-designed systems can reduce inequality while supporting economic dynamism, while poorly designed ones might create inefficiencies or unintended consequences.

Asset-Building and Wealth Creation

Beyond income supports, policies that help broader populations build assets can address wealth inequality more directly:

Baby bonds or children’s savings accounts established at birth with progressive initial deposits and matching contributions could give every child a financial foundation for education, homeownership, or entrepreneurship in adulthood.

First-time homebuyer supports through down payment assistance or preferential mortgage terms can help families begin building housing wealth, historically a primary wealth-building vehicle for the middle class.

Retirement security enhancement through expanded Social Security, universal retirement savings accounts with automatic enrollment, or guaranteed retirement accounts could ensure that more workers build retirement assets.

Community development financial institutions with specific missions to serve underbanked communities can expand credit access for small business formation and asset-building in historically excluded populations.

These approaches focus on broadening asset ownership rather than simply redistributing existing wealth, potentially creating broader stakeholder interests in economic growth and capital appreciation.

Institutional and Governance Reforms

Addressing how economic and political power interact may be necessary for sustaining more equitable outcomes:

Campaign finance reform to reduce the influence of concentrated wealth in political processes could help ensure policies reflect broader interests rather than those of the most affluent.

Antitrust enforcement and competition policy to address market concentration can prevent monopolistic practices that suppress wages, raise consumer prices, or create barriers to new business formation.

Financial regulation focusing on systemic stability, consumer protection, and broad access to financial services can prevent extractive practices that redistribute wealth upward.

Tax enforcement to address evasion and avoidance, particularly through international mechanisms like offshore tax havens, can ensure that existing tax policies function as intended.

Implementation Challenges and Considerations

While researchers have identified many promising approaches to reducing inequality, Implementing them effectively involves Navigating significant challenges:

Balancing Efficiency and Equity

Policy design must consider potential Trade-offs between Distributional goals and economic efficiency. Well-designed interventions can actually enhance both equity and efficiency—for instance, by developing human potential that would otherwise be wasted—but poorly designed ones might create Counterproductive incentives or Unintended consequences.

Globalization Constraints

In an Interconnected global economy, some policy approaches face practical limitations. For instance, Excessively high tax rates in one jurisdiction without international Coordination might trigger capital flight or tax Avoidance through Offshore arrangements. Addressing these challenges may require greater international cooperation on tax policy, labor standards, and financial regulation.

Technological Change Management

As Automation and artificial intelligence transform work, Inequality pressures may Intensify without Deliberate policy responses. Ensuring that technological productivity gains benefit broader populations—not just capital owners and highly skilled workers—represents a crucial challenge for Maintaining shared Prosperity.

Political Feasibility

Perhaps the greatest challenge involves building political coalitions capable of Enacting significant reforms when those Benefiting from current arrangements often have Disproportionate influence. Successful reform efforts typically require Broad-based movements that effectively Articulate how reducing extreme Inequality se